And all earlier drafts of my book included a sort of big-picture retelling of those events, focusing on signature dissenters like Hugh Thompson and Ron Ridenhour. Now that I’ll be referring to those events ONLY in a leaner, character-based narrative, I wanted this blog to have this version, of which I am pretty proud.

And all earlier drafts of my book included a sort of big-picture retelling of those events, focusing on signature dissenters like Hugh Thompson and Ron Ridenhour. Now that I’ll be referring to those events ONLY in a leaner, character-based narrative, I wanted this blog to have this version, of which I am pretty proud.

I do wonder now who’s followed up with the quieter dissenters – the guys who said no. Any miilitary reporters want to tell me?

“But these are human beings, unarmed civilians, sir”

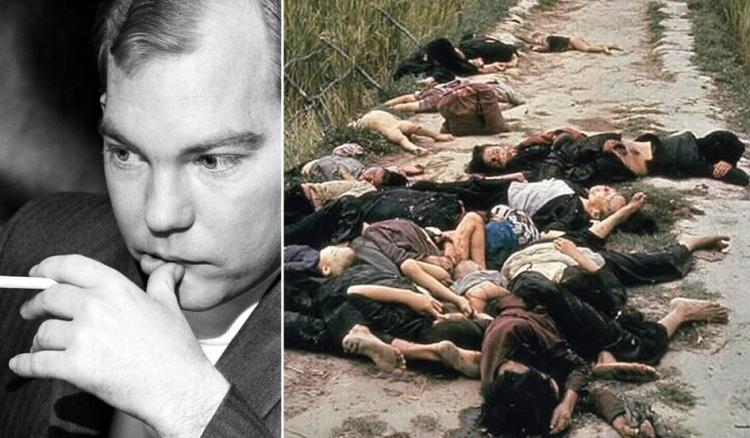

At the end of 1969, reports flooded the U.S. newspapers about an incident not dissimilar to what had apparently happened at Liberty Bridge, bearing color photos by Army photographer Robert Haeberle, taken on March 16, 1968 in the hamlet of My Lai.

Nowadays, the name “My Lai” evokes Auschwitz, calling to mind images with which the mind has trouble coping, and Nurnberg, the small city where Nazi war ctiminals were put on trial. But the story of My Lai is often also a story of a string of dissenters.

Warrant officer Hugh Thompson didn’t plan to be one, flying over the province in support of Task Force Barker, 1st Infantry of the Americal Division. Formed in 1942 to defend the South Pacific island New Caledonia, Americal was remembered at Guadalcanal, Papua New Guinea and Quang-Tri.

The week of March 15, Task Force Barker’s mission was relatively straightforward: to wipe out the Vietcong 48th Infantry. “The operation was to commence at 0725 hours on 16 March 1968 with a short artillery preparation, following which C/1-20 Inf was to combat assault into an LZ immediately west of My Lai (4) and then sweep east through the subhamlet.”i

Despite the copies of the Geneva Conventions soldiers were instructed to carry, the Division was also operating under orders that which exempted “hot spots” like My Lai from the Conventions’ protection. Directive 525-3 from the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), “Combat Operations: Minimising Noncombatant Battle Casualties,” carefully noted that “Specified strike zones should be configured to exclude populated areas, except those in accepted VC bases.”ii

As he flew over the area, Thompson knew that Charlie Company had just lost 34 men in a single grenade attack. He also knew that orders since Tet named women and children as possible Vietcong. But Thompson and his crew were still astonished at what they saw from their helicopter on the 16th: “Everywhere we’d look, we’d see bodies. These were infants, two-, three-, four-, five-year-olds, women, very old men, no draft-age people whatsoever.”iii As one platoon turned their guns full force on a farmer, U.S. Army photographer Haeberle was horrified: “”They just kept shooting at her. You could see the bones flying in the air chip by chip.” Haeberle carefully photographed those corpse-filled huts in full color, even before Thompson arrived.

Thompson also left the task of investigating what had happened to his superiors: the command, he reasoned, “didn’t need me there to court-martial these renegades.”iv One of Calley’s sergeants, Michael Bernhardt, said that they were expecting an investigation, but “Some colonel came down to the firebase where we were stationed and asked about it, but we heard no further.” v The action’s official post-operation Army communique made no mention of civilian casualties, numbering the Viet Cong body count at 128 and noting that Charlie Company had recovered two M-I rifles, a carbine, a short-wave radio and enemy documents. vi

As for Charlie Company, “[Capt. Ernest ]Medina …called me over to the command post and asked me not to write my Congressman,” said Bernhardt,vii said one of a handful of Charlie Company soldiers who had not taken part in the massacre. The “lawful disobedience” practiced by this group was as varied as the war itself.

Sgt. Bunning told his squad leader that “I wasn’t going to shoot any of these women and kids.” Stephen Carter refused to shoot a woman holding a baby coming out of her hut. Paul Meadlo, who did participate when pressured by Calley, was described as “sobbing and shouting and saying he wanted nothing to do with this.” viii A year later, Meadlo told reporters who asked how: “From the first day we go in the service, the very first day, we all learned to take orders and not to refuse any kind of order from a noncommissioned officer.” Their roles that day appears to have been influenced by multiple factors including their age, whether their MOS had them were carrying light, trigger-easy M16s, their proximity to the actual giving of the illegal orders, and their personal perspective on the issue of war crimes.ix

But even the refusers never told the outside world to what had happened. It took a year before that year-long embargo was broken.

Spc. Thomas Glen, from the 11th Light Infantry, had tried in late 1968, writing the staff of Gen. Creighton Abrams that such behavior “cannot be overlooked, but can through a more firm implementation of the codes of Military Assistance Command Vietnam and the Geneva Conventions, perhaps be eradicated.”x Abrams never responded, but his assistant Major Colin Powell reprimanded Glen for speaking so vaguely, and added that “There may be isolated cases of mistreatment of civilians and POWs, [but] this by no means reflects the general attitude throughout the Division.” Just as Powell was writing, Corporal Ron Ridenhour was preparing to prove him wrong.

Ridenhour had learned the news from an old friend who had joined Charlie Company a few months earlier: “ Hey man did you hear what we did at Pinkville?…. Men, women and kids, everybody, we killed them all….We didn’t leave anybody alive, at least we didn’t intend to.” xi”

Seized by “an instantaneous recognition and collateral determination that this was something too horrible, almost, to comprehend and that I wasn’t gonna be a part of it,” Ridenhour tracked down members of Charlie Company one by one. “They couldn’t stop talking,” Ridenhour said later. “They were horrified that it had occurred, that they had been there, and in the instances of all of these men, that they had participated in some way.”

In March 1969, Ridenhour wrote a letter as specific as Glen’s was vague, naming every soldier he’d interviewed and detailed their accounts, including that Capt. Medina had warned soldiers never to speak about My Lai. “I remain irrevocably persuaded,” he told the Joint Chiefs, the President and every TV network, ‘that … we must press forward a widespread and public investigation of this matter. “xii

At the closed set of hearings that resulted, Hugh Thompson and others identified the man directing the massacre as Calley. Calley insisted that he was implementing the mission set forth by his commander Captain Medina, but he was still the only one indicted for the murder of “one hundred and nine Oriental human beings.”

A freelance Pentagon reporter named Seymour Hersh soon saw the indictment. “My first thought was not wow this will end the war, but What a story!” When he went to Fort Benning to find Calley, Ron Ridenhour “gave me a company roster, and I began to find the kids.”

The resulting interviews and photos ran nationwide — the week of the moon landing in July 1969. So it took some time for all of us to get this glimpse of what we know now was standard operating procedure during that war.

It certainly didn’t get mentioned during all the laudatory moon-shot retrospectives. But attention still, I think, must be paid.

(Photo: Stephen Carter and My Lai, Newsweek)

is

ii Via Gareth Porter, “ My Lai Probe Hid Policy that Led to Massacre.” Interpress Service, March 15, 2008.

iii From remarks at “My Lai 25 Years After: Facing the Darkness, Healing the Wounds,” Tulane University, 1994. Accessed via University of Missouri (Kansas City) digital resource, “Famous American Trials: The My Lai Courts-Martial,1970.” http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/mylai/mylai.htm, December 2008.

iv Fall 2003 Lecture, Center for the Study of Professional Military Ethics, United States Naval Academy, Annapolis MD.

v Seymour Hersh, Hamlet Attack Called “Point-Blank Murder”. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 20. 1969.

vi Seymour Hersh, “Lieutenant Accused of Murdering 109 Civilians.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 13, 1969, p. A1.

vii Hersh, November 20. op. cit.

viii Peers final report….

ix Rives Duncan, “What Went Right at My Lai: An Analysis of Habitus and Character in Lawful Disobedience.” Ph.D. diss., Temple University, 1992. I owe Major Duncan full credit for use of the term “lawful disobedience,” here and elsewhere.

x Via Robert Parry and Norman Solomon, “Colin Powell and My Lai.”Consortium News, October 1996.

xi “My Lai 25 Years After,” op.cit.

xii Ibid.

Reblogged this on I Ain't Marchin' Anymore and commented:

Tomorrow’s the 16th anniversary of the actual massacre: the day Medina and Callley went postal and killed hundreds. We have since learned that that was far from unusual.